MPC

Multisectoral Coordination for Health Security Preparedness

Document Library

Background

Countries must be better prepared to detect and respond to public health threats in order to prevent public health emergencies and the devastating impact they can have on people’s lives and well-being, as well as on travel and trade, national economies, and society as a whole. Public health challenges are complex and cannot be effectively addressed by one sector alone.

A holistic, multisectoral and multidisciplinary approach is needed for addressing gaps and advancing coordination for health emergency preparedness and health security and is essential for the implementation of the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005).

Health emergencies, including disasters, take a heavy toll on populations around the globe. Human and animal diseases, chemical, radiological and nuclear accidents, and natural disasters cause ill-health, disability, loss of lives, food insecurity, environmental damage, displacement, and destabilization of trade and economic development, as well as of societies as whole. Diseases can spread, and they can do so even more significantly where health systems are fragile or are faced with newly emerging and re-emerging diseases, as seen in recent outbreaks of Ebola virus disease, Zika virus disease, yellow fever, cholera, and COVID-19, affecting entire countries and regions. As a result, health security is high on the international agenda. Health security is a continuous process in which action, financing, partnerships, and political commitment must be sustained.

The IHR (2005) represents the legal basis for multisectoral coordination for emergency preparedness and health security. WHO promotes the participation of all relevant sectors to contribute to the improvement of the capacity of States Parties to prevent, detect and respond to public health emergencies of international concern and accelerate the implementation of the IHR (2005). An intersectoral approach is among the guiding principles for implementation of the IHR (2005) set out in a report by the WHO Secretariat to the Seventieth World Health Assembly, May 2017, which states: “Responding to public health security threats requires a multisectoral, coordinated approach (for example with agriculture, transport, tourism, and finance sectors)”. Furthermore, as stipulated in the 2021 World Health Assembly Resolution, WHA 74.7, there is the need “to adopt an all-hazard, multisectoral, coordinated approach in preparedness for health emergencies, recognizing the links between human, animal and environmental health and the need for a One Health approach”.

Under the WHO Thirteenth General Programme of Work 2019–2023, the WHO Health Emergencies Programme has an integral role in contributing to the strategic priority of 1 billion more people being better protected from health emergencies by building and sustaining the national, regional, and global capacities required to keep the world safe from health emergencies. In support of implementation of the Thirteenth General Programme of Work and attainment of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, the MPC provides evidence-based information on how to establish functional multisectoral coordination, primarily within but importantly also beyond the government structures, for countries to better prevent, detect and respond to all potential public health threats.

MPC Framework

The multisectoral preparedness coordination (MPC) framework was developed by the Multisectoral Engagement for Health Security Unit, led by Ludy Suryantoro, Unit Lead, and Romina Stelter, Technical Officer, with the support of Stella Chungong, Director, Health Security Preparedness Department, and Jaouad Mahjour, Assistant Director-General, Emergency Preparedness and International Health Regulations. It followed the expert roundtable on multisectoral preparedness coordination (MPC) for International Health Regulations (IHR 2005) and health security which was convened by the World Health Organization (WHO), at the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) headquarters in Paris on 4–5 October 2018. The aim of this roudtable was to develop a guide for multisectoral preparedness coordination for IHR (2005) and health security to provide Member States with tools to support the practical implementation of national action plans for health security. Thirty-seven representatives from Member States, international organizations, and non-state actors (NSAs) discussed best practices, models and lessons learnt from countries’ experience in MPC, to inform key content and strategy of the guide.

The MPC framework provides States Parties, ministries, and relevant sectors and stakeholders with an overview of the key elements for overarching, all- hazard, multisectoral coordination for emergency preparedness and health security, informed by best practices, country case studies and technical input from an expert group. Those elements form the basis of the MPC framework that aims at improving coordination among relevant public stakeholders, particularly actors beyond the traditional health sector, such as finance, foreign affairs, interior and defence ministries, national parliaments, non-State actors, and the private sector, including travel, trade, transport, and tourism.

The MPC framework complements the International Health Regulations Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (IHR MEF) and contributes to the strategic goal in the WHO Thirteenth General Programme of Work of 1 billion more people better protected from health emergencies and supports the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 3 – ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

It discusses key elements for effective multisectoral coordination for health emergency preparedness, including high-level political commitment, country ownership and leadership, and formalizing mechanisms that contribute to multisectoral preparedness coordination.

Parliament’s role in strengthening health security preparedness

The Resolution on Achieving universal health coverage by 2030: The role of parliaments in ensuring the right to health was adopted during the 141st IPU Assembly in Belgrade, Serbia, held between the 13th and the 17th of October 2019. The Resolution acknowledged the importance of a multisectoral coordination approach to health and stated, “Also urges parliaments to address the political, social, economic, environmental and climate determinants of health as enablers and prerequisites for sustainable development, and to promote a multisectoral approach to health;”.

Resilient health systems are vital for preparing for and responding to emergencies, and for maintaining essential health services during a crisis. The IHR (2005) are an important tool of international law, reflecting the commitment by States to prevent, detect and respond to emergency health risks.

Parliaments and parliamentarians play a unique and powerful role in achieving preparedness through their various responsibilities: law-making, oversight, budgetary allocation and citizen representation. High-level reviews of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic emphasize the importance of State capacity, social trust and leadership when it comes to preparedness. Parliaments and parliamentarians are extremely well positioned to help build and strengthen all three.

The 34th Handbook for Parliamentarians on Strengthening health security preparedness: The International Health Regulations (2005) prepared by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Inter- Parliamentary Union (IPU), was created to enhance parliamentary contributions to health-security preparedness. It is designed to be used by parliamentarians and parliamentary staff as they consider important aspects of preparedness that need to be established or strengthened at all levels including communities. The handbook contains key questions that can help guide parliamentarians in their capacity-building efforts.

Civil-Military Collaboration for Health Emergency Preparedness

To ensure effective civil–military health collaboration that supports health emergency preparedness interventions required to combat existing or potential threats, and for longer-term health security capacity-building, it is critical to identify pathways for partnership well before a response to a health emergency is required. To this end, WHO together with Member States and partners developed the National civil–military health collaboration framework for strengthening health emergency preparedness. The aim of this framework is to provide the public health sector and military actors and services at the national level with guidance for establishing, advancing, and maintaining collaboration and coordination, with the focus on country core capacities required to effectively prevent, detect, respond to, recover from and build back better after health emergencies.

Development of this framework was initiated following a meeting on “Managing future global public health risks by strengthening collaboration between civilian and military health services” (Jakarta, 24–26 October 2017), which brought together more than 160 public health and security representatives from 44 countries, international organizations, partners and donors. Guiding principles were agreed on how to strengthen collaboration between the security and civilian health sectors in line with the commitment made by members of the Group of 20 to strengthen global health security and accelerate the implementation of the IHR (2005). Furthermore, in December of 2018, the WHO Secretariat (Multisectoral Engagement for Health Security Unit) convened a global technical consultation on national cross-sectoral collaboration between security and health sectors in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. The Technical Consultation included 51 expert participants representing 19 Member States, as well as partners, WHO and non-governmental actors. The participants emphasized that it is critical to ensure civil-military collaboration for preparedness, not just joint action in times of emergency. A key point of discussion was to ensure that agreements are flexible and tailored to the national context. Militaries have different roles and competencies in different countries. Participants agreed that militaries cannot be seen only as a last resort, and they have capabilities for preparedness that go far beyond that of rapid response to emergencies. A draft version of the NCF Framework was circulated to all participants who discussed it at length and provided valuable feedback on it.

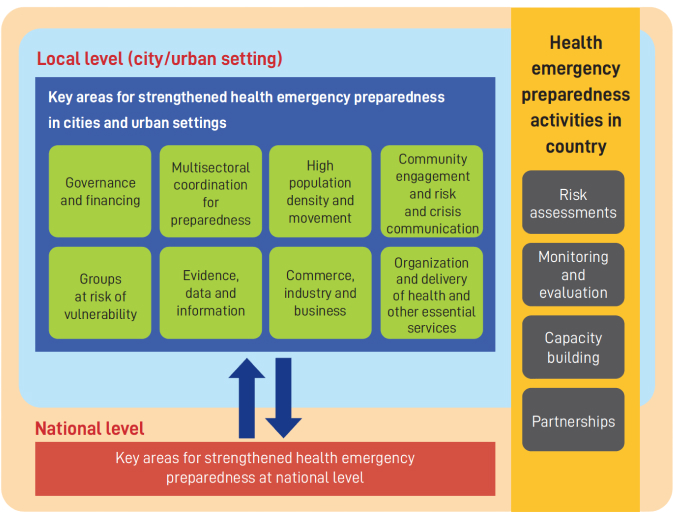

Health Emergency Preparedness in Cities and Urban Settings

Cities and urban settings are crucial to preventing, preparing for, responding to, and recovering from health emergencies, and therefore enhancing the focus on urban settings is necessary for countries pursuing improved overall health security. Urban areas, especially cities, have unique vulnerabilities that need to be addressed and accounted for in health emergency preparedness.

Strengthening health emergency preparedness at the urban level requires the support of multiple sectors and partners beyond health at all levels – from global to national, subnational and local levels, including within cities and urban settings. Coordination across sectors and partners is vital to ensure coherence in preparedness activities and increase resilience, and should include all actors, including the private sector and civil society. This requires the use of whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches, with coordination often coming from the highest level of each government, including the offices of city leaders (e.g. Mayors and Governors), as well as potentially mainstreaming preparedness across departments at the operational level.

Multisectoral preparedness coordination may face challenges partly due to siloes existing at different levels of government – national, regional, and local, including those arising from the fundamental foundations and structure of organizations and institutions. Some stakeholders also may not be aware of the relevance of emergency preparedness for themselves, leading to less willingness to collaborate, especially once the acute phase of an emergency is over. There is therefore a benefit in including these sectors and actors in simulation exercises and other drills, as these activities promote coordination, build relationships, open soft and informal avenues for communication, and help facilitate the working cultures necessary for multisectoral coordination.

Urban Preparedness

Foreign Policy for Health

In today’s interconnected world foreign policy and international relations have a direct influence on how countries can work together for health emergency preparedness. Epidemics can lead to economic decline, social destabilization and unrest, with implications for national and international security. Travel and trade sanctions imposed by governments on countries affected by outbreaks can harm economies and relations. As viruses and diseases do not respect borders, public health needs to be understood as a decisive factor in international diplomacy, with foreign policy bearing a responsibility for strengthening global health security. Health emergency preparedness is a matter of national and global security and is critical in enhancing collaboration on cross-border health security threats. Collaborative foreign policy on global health allows for better access to information, technologies, medicines and vaccines, and improves accessibility to these resources by vulnerable populations.

This includes both building up preparedness capacities within countries and enabling access to capacities in other countries when health emergencies occur. Foreign policy can also serve to mitigate the potential threat to national and global health security of deliberate actions, such as intentional release of biological agents, and can act as a bridge for peace.

MPC Online Training Tool

The MPC Online Training Tool provides users with key information about multisectoral preparedness coordination, sets out specific learning objectives, and is split into 5 modules to facilitate learning and the achievement of the objectives. It is designed to help users, both health and non-health stakeholders, familiarize with the topics.

The first module provides an overview and contextualizes the multisectoral preparedness coordination framework by explaining its critical role in emergency preparedness. Module 2 identifies the relevant stakeholders for health emergency preparedness and health security. Module 3 outlines how to establish the necessary high-level political commitment and support. Module 4 explains how to formalize and develop multisectoral preparedness coordination structures. Whereas module 5 shows the key factors, such as communication, funding, and transparency, needed to successfully implement MPC.