Header Image

Health Emergency Preparedness in Cities and Urban Settings

Strengthening health emergency preparedness in cities and urban settings

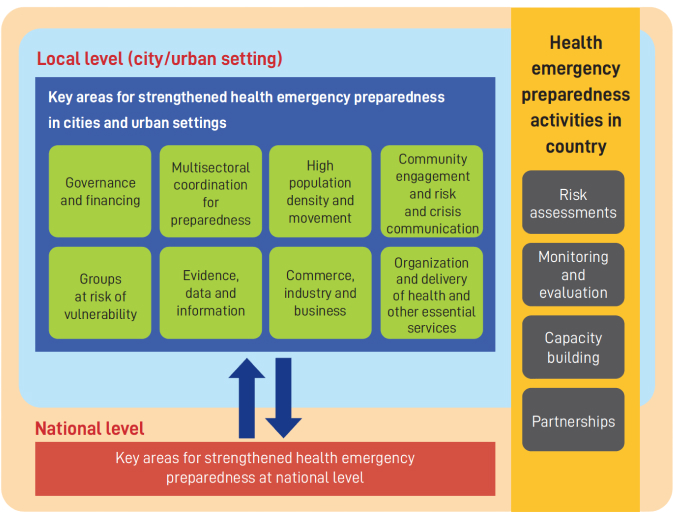

Cities and urban settings are crucial to preventing, preparing for, responding to, and recovering from health emergencies, and therefore enhancing the focus on urban settings is necessary for countries pursuing improved overall health security.

Urban areas, especially cities, have unique vulnerabilities that need to be addressed and accounted for in health emergency preparedness. An unprepared urban setting is more vulnerable to the catastrophic effects of health emergencies and can exacerbate the spread of diseases, whilst they are also very often the frontline for response efforts. This has been seen in past disease outbreaks, as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is therefore crucial that health emergency preparedness in cities and urban settings is addressed through contextualized policy development, capacity building, and concrete activities undertaken at the national, subnational, and city levels.

At the 75th World Health Assembly (WHA) in May 2022, WHO Member States underlined the importance of this area through the adoption of resolution WHA 75.7 on Strengthening Health Emergency Preparedness and Response in Cities and Urban Settings. It was co-sponsored by 18 countries from across all six WHO regions, underlining the broad support for WHO to strengthen its work in this area to support countries.

This built upon on the Member State request in WHA Resolution 73.8 to enhance a focus on urban preparedness, which led to WHO convening, jointly with the Government of Singapore, a Technical Working Group on the topic in early 2021. An outcome of this is the WHO Framework on Strengthening Health Emergency Preparedness in Cities and Urban Settings, intended to support member states and policymakers at the national and city levels. The Framework is supported by the guidance document Strengthening health emergency preparedness in cities and urban settings: guidance for national and local authorities.

Key areas of focus for strengthening health emergency preparedness in cities and urban settings

Governance and financing for health emergency preparedness

Governance and financing are both key to effective health emergency preparedness. Focusing on preparedness at the sub-national level (such as the city/urban level) adds a layer of complexity from a governance perspective. It requires robust and effective mechanisms by which the different levels of government involved (e.g., national, regional, local) can coordinate, and a clear delineation of roles, responsibilities and accountabilities. Due to the nature of emergencies, these may differ from ‘peacetime’, and it is important that systems are ready to adapt for response when necessary. Any existing legislative gaps need to be identified and closed.

The multiple layers of governance involved may also complicate financing, as budget lines, financing flows, and the distribution of funds may be different in an emergency. This is further complicated if there is a discrepancy between political agendas at different levels of governance. It is therefore important that mechanisms are in place to ensure funds can be released and redistributed as necessary in an emergency, without delays caused by the extra layers of governance involved.

Multisectoral coordination for preparedness

Strengthening health emergency preparedness at the urban level requires the support of multiple sectors and partners beyond health at all levels – from global to national, subnational, and local levels, including within cities and urban settings. Coordination across sectors and partners is vital to ensure coherence in preparedness activities and increase resilience, and should include all actors, including the private sector and civil society.

This requires the use of whole-o government and whole-of-society approaches, with coordination often coming from the highest level of each government, including the offices of city leaders (e.g., Mayors and Governors), a well as potentially mainstreaming preparedness across departments at the operational level.

High population density and movement

Cities and urban settings often contain large numbers of people, leading to high population densities and crowding where people live, play and work. This increases the chance of being in crowded situations and means that health emergencies can impact a larger number of people at once, especially when it involves infectious diseases. In epidemics, especially those spread by droplets or aerosols, this increases the risk of disease spread. This includes shared spaces and public areas with high human traffic or are frequently used, and public transportation. Crowded situations often found in cities and urban settings include mass gatherings such as religious events, concerts and sporting events, or poorly ventilated areas such as bars and nightclubs.

Other locations such as nursing/care homes, dense forms of housing, refugee camps and commercial venues such as shopping centres may also pose risks, as well as mass gathering events, that often take place within cities. Further, overurbanization has also led to a proliferation of informal settlements / slums emerging, where population densities also tend to be higher, and they also rely on communal and often inadequate WASH facilities. Mobility between the mobile populations existing in these congregation points and local/fixed populations also risks the further spread of communicable diseases.

Community engagement and risk and crisis communication

As health threats emerge at local levels, communities play an important role in health emergency preparedness and risk reduction. Community members participating from the earliest stages of policy and programme formulation help clarify local priorities, challenges, and pathways for practical and sustainable action. This requires sustained and meaningful community involvement (beyond just engagement), such as through community led-approaches, participatory governance mechanisms, social participation methods, and the co-creation of solutions.

Often, there is insufficient engagement, integration, and protection of communities in cities and urban settings in health emergency preparedness plans. Whilst engagement can be challenging for a variety of reasons, the perspectives which they offer enhance policy and programme development and ensure effective translation and implementation. Doing so also engenders trust in governments and public systems at all levels. Effective involvement and engagement of communities cannot be achieved without effective communication, tailored to the respective specific target audience.

Groups at risk of vulnerability

Cities and urban settings are centres for inequalities and groups at risk of vulnerability. For instance, it is estimated that 70 percent of people displaced across or within national borders live in cities, and migrants are overrepresented among the urban poor (6). Aside from vulnerabilities specific to certain diseases or emergencies (e.g., Zika virus and pregnancy, COVID-19, and persons with medical comorbidities), there are also persons that are generally vulnerable to the direct or indirect impacts of health emergencies. Given their proximity to people, city governance structures are often best placed to identify those at risk of vulnerability and those most in need of targeted preparedness efforts.

Preparedness for a health emergency in an urban setting includes anticipating and preparing for vulnerabilities linked to the direct or indirect impact of all-hazards. For example, restricted movements risk livelihoods of those dependent on the informal economy, as well as may hinder timely access to health services. Countries and their local communities are as strong as their weakest link, and preparedness and response plans will not be as effective if the needs of vulnerable populations are not looked after. This includes building community resilience to the impacts of health emergencies. In this regard, trusted community leaders and civil society organizations including those with established initiatives in working with and supporting vulnerable populations, may serve as an important resource.

Evidence, data and information

Data represents a challenge to cities globally; sometimes it is missing or limited, or when available, fragmented, siloed, or outdated. However, local authorities of cities and urban settings often hold a wealth of data which should be used to strengthen health emergency preparedness and response. This includes but is not limited to, urban settlement data such as demographics, informal settlements and other vulnerable communities, housing and zoning, transport networks, public and private facilities and resources, emergency, disaster and risk management, for example evacuation routes, supply chains information on current and future hazards, vulnerabilities, capacities, and scenarios, and population demographics. Such information can help guide efforts to improve preparedness and build community resilience, including leveraging crowd sourced data or sentinel sites for surveillance and sense-making. Aside from event detection, it can help monitor impact and assess the uptake and effectiveness of response measures and recommendations.

Further, health considerations, including needs for emergency preparedness and response, can be better integrated into designing and building sustainable cities for the future. Where possible, data should be disaggregated by sex.

Commerce, industry and business

Cities and urban settings are also centres for commerce and many industries, employing large numbers of individuals. They are also responsible for places where groups of people spend a substantial amount of time each day. In addition to this, many local businesses are community-centred with good networks, relationships and local knowledge. Therefore, businesses and corporations can serve as a partner and resource for national and local governments in preparing for health emergencies, in particularly when it comes to innovating in order to better prepare, detect and respond to novel and emerging challenges posed by future and ongoing health emergencies.

This can cover a broad range of areas, including risk communication and risk management. Examples include occupational health and safety, including prevention of zoonosis, infection and contamination of food at live animal markets; instituting remote working arrangements where possible, and implementing public health measures to reduce the spread of infectious diseases at the workplace where remote working is not possible; providing resources in an emergency, such as the repurposing of manufacturing plants to producing personal protective equipment and the reorganization of commercial spaces or services to accommodate public health measures; and supporting risk communication and public engagement, through both customers and employees, around public health measures.

They are also important for maintaining logistics and supply chains for the continued provision of essential services, for example for food and medical supplies, or the repurposing of manufacturing plants and using hotel rooms for quarantine and temporary housing for the homeless. Furthermore, without engaging national and local private business and enterprises, it is not possible to achieve the adequate support to key workers, transport systems, reorganization of public spaces / business models that is needed in order to maintain business continuity and continue providing adapted business services to local communities during a health emergency.

Organisation and delivery of health and other essential services

Health systems, in particular the delivery of health services, play a critical role in preparedness, response and recovery for all types of hazards. These range from primary and community care to tertiary level hospitals. For example, surveillance, detection and notification; vaccinations to prevent outbreaks, including prophylaxis of major zoonotic diseases in animals; infection prevention and control to prevent further spread of disease; and treatment to save lives are all dependent on the health system. Urban settings, especially major cities, tend to hold a full suite of services that can include academic hospitals with health specialists, advanced diagnostics, medical equipment, supplies, and intensive care units, all of which are crucial capacity in an emergency.

However, there can also be huge disparities and gaps in access to services in urban settings, especially by those of lower socio-economic status and hard-to-reach populations, leading to unequal health outcomes, delays in event reporting and contact tracing.

Beyond health facilities, cities and urban areas also often host other critical infrastructure that needs to remain operational regardless of the emergency situation (e.g., PoEs, power and freshwater plants, security & safety services, communication & ICT infrastructure, financial organizations, and others). Given the breadth and variety of services that exist in cities, it is important that the organisation of services is also organised around health security objectives. This requires collaboration across services, and a holistic and multisectoral approach to service delivery.

Videos

On This Page

- Strengthening health emergency preparedness in cities and urban settings

- Key areas of focus for strengthening health emergency preparedness in cities and urban settings

- Governance and financing for health emergency preparedness

- Multisectoral coordination for preparedness

- High population density and movement

- Community engagement and risk and crisis communication

- Groups at risk of vulnerability

- Evidence, data and information

- Commerce, industry and business

- Organisation and delivery of health and other essential services

- Videos