The Sehatmandi programme is the backbone of Afghanistan’s health system, providing care for millions of people through 2,331 health facilities. Since the Taliban gained power, major funding for the programme has been withdrawn.

Without adequate funding, Sehatmandi health facilities are breaking down, affecting the availability of basic and lifesaving health care nationwide, as well as humanitarian assistance, polio eradication and COVID-19 vaccination efforts.

The Sehatmandi programme, if fully funded, will continue to provide essential and life-saving care to all Afghans. The hard-fought gains made in life expectancy, and maternal and child mortality over the past two decades will be kept.

Afghanistan’s health system is on the brink of collapse, and WHO is calling on international donors to rapidly finance the Sehatmandi programme, as they have done for almost two decades.

“We need to find innovative approaches to help millions of people including children, women and men in Afghanistan during this complex humanitarian crisis that is exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the on-going severe drought, combined with severe economic downturn. It is urgent, and the international community has a responsibility to act now.”

“The recent funding pause by key donors to the country's biggest health programme (Sehatmandi) will cause the majority of the public health facilities to close. As a result, more mothers, infants and children will die of reduced access to essential health care. WHO is determined to work with partners in identifying a sustainable solution with the support of donors to maintain and scale up the lifesaving interventions when needed in the country.”

“Bringing together in one package, health, clinical and surgical interventions, population public health interventions and inter-sectoral policy interventions, will go a long way towards helping improve the health of all Afghans. Sound and efficient implementation of the whole package will also help make the health system even more resilient, especially to disease [outbreaks] and injury shocks, and will also contribute to having a more responsive and inclusive health system.”

THE LONG READ

Ayesha, 29, is a midwife in a rural health facility in Afghanistan. She graduated from the provincial midwifery school supported by the government’s Sehatmandi programme, which provides essential primary care services including for maternal, newborn and child health. These vital health services that save the lives of many in the community have come under severe threat.

“I was born in a very remote district where health facilities were not available. I witnessed many pregnant mothers dying because there was no health care facility at my village or on the way to hospitals, located more than 50 km away. I decided to become a midwife and serve the women and children in the villages. I love my job and attend numerous institutional deliveries, and have contributed to the reduction of maternal mortality,” said Ayesha.

The primary care facility in the village is vital, serving 58,000 people including 13,340 women of childbearing age and 11,600 children under-five. Importantly, it provides emergency obstetric care, including Caesarean section services. Without this, women would have to travel far, and put themselves and their babies at risk.

Due to a lack of funding, staff in the health facility have not received their salaries for months, the clinic is faced with shortages of medicine and supplies, and patients are not able to access the essential health services they need. If this facility closes down, increasing ill health and mortality is inevitable. The facility’s struggles are not unique. The situation is replicated across the country because the Sehatmandi programme is no longer able to receive appropriate financial support due to the change in Afghanistan’s government. Previously funded by the World Bank, the European Commission, and USAID, there are now serious challenges to continuing these vital primary health care services. As of 15 January 2022, the country has received funding to help cover immediate needs for the early part of the year. More funds are needed to urgently fill remaining gaps and to support the country’s heath system in sustaining the delivery of essential services.

The population is also suffering due to a recent drought that has affected crops and livestock. This, combined with rising food prices and the collapse of public services, led to acute food insecurity for nearly 19 million people in September and October 2021.

The Sehatmandi programme

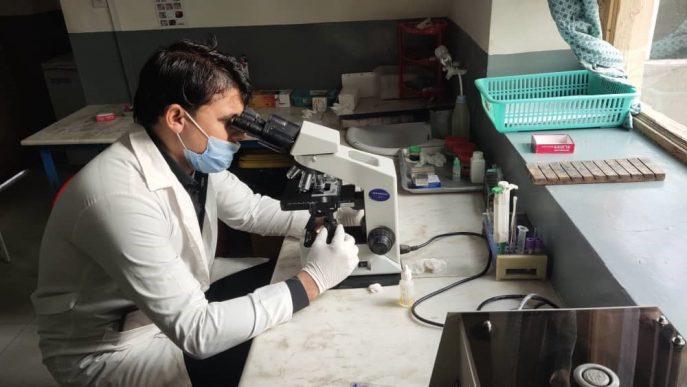

The Sehatmandi programme is the backbone of Afghanistan’s health system. It provides affordable health care for millions of people through 2,331 health facilities in 34 provinces, covering 64% of all public health facilities. The programme employs more than 24,000 health workers, of which 8,000 are women.

The Sehatmandi programme originated as the System Enhancement for Health Action in Transition (SEHAT) Project from 2013-2018, and transformed into the Sehatmandi programme in 2018. Equity principles have been central in this approach, allowing harmonization across the entire country with the aim of increasing health service coverage, especially for rural populations.

Because of a funding pause, most of the Sehatmandi health facilities are not fully functional and have stock-outs of essential medicines. The breakdown in health facilities is affecting the availability of basic and essential health services, as well as humanitarian assistance, polio eradication and COVID-19 vaccination efforts.

“I visited the public health facility to receive treatment but due to the shortage of medicines in the clinic, I didn’t get the proper medication. Unfortunately, many patients are disappointed because of the scarcity of medicines and supplies,” said Nasima, 32, a housewife in another Province.

For two decades in Afghanistan, life expectancy has risen, and maternal, newborn and child deaths have dramatically decreased. Today, the population’s health is seriously under threat. All the progress in health outcomes may be lost. WHO is urgently calling for international donors to step up and find an alternative funding mechanism for this crucial primary health care initiative.