Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Interventions

Health emergencies and disasters increase risk of developing mental health and psychosocial problems [1]. However, timely Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) can reduce these risks and promote recovery and resilience [2]. WHO co-chairs the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Reference Group on MHPSS in Emergency Settings that provides advice and support to organizations working in emergencies and to country-level MHPSS technical working groups in more than 50 countries [2].

In response to the strong need for MHPSS interventions in all phases of emergencies, including preparedness, prevention, response and recovery, IASC reference Group on MHPSS developed the IASC Guidelines for MHPSS in Emergency Settings in 2007. The guidelines describe MHPSS as ‘any type of local or outside support that aims to protect or promote psychosocial well-being and/or prevent or treat mental health condition’ [3]. The guidelines are to enable humanitarian actors and communities to plan, establish and implement a set of minimum multi-sectoral responses to protect and improve people’s mental health and psychosocial well-being as soon as possible in an emergency.

Effective MHPSS interventions (including early detection) of mental conditions should be delivered in the right time and also for the right period of time. Despite the mounting evidence highlights the need to address both acute and long-term mental health impact, challenge remained to elucidate the suitable timeframe for various MHPSS interventions [1]. However, current evidence and knowledge demonstrates MHPSS is important in all phases of disasters: preparedness and prevention, response and recovery.

Preparedness and Prevention Phase

Increased risk and prevalence of mental health problems related to emergencies highlighted the need of MHPSS interventions in the Preparedness and Prevention phase. Thus disaster risk management approaches have increasingly shifted from response focused actions to preventative and proactive actions to reduce mental health risks before hazardous events occur. Despite the shift, MHPSS has largely been overlooked in preparedness and prevention action. However there are recent efforts to develop MHPSS guidelines and training tools for this phase.

Relevant Tools

-

Technical Note Linking DRR and MHPSS: Practical Tools, Approaches and Case Studies

The IASC published a ‘Technical Note Linking DRR and MHPSS: Practical Tools, Approaches and Case Studies’ in 2021. This global guideline outlines key actions to promote MHPSS preparedness prior to emergencies and reduce risks to mental health and psychosocial well-being through risk reduction and management.

Acute/Immediate Response Phase

People may experience severe stress reactions immediately after a crisis but it does not always lead to mental health conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety. However, some may complain poor sleep quality, heightened suicidal risk and acute stress, and a minority may go on to develop mental health conditions [3].

Fortunately, suffering can be reduced and mental health and psychosocial well-being can be promoted through varied forms of MHPSS, which can be effective, low-cost and low-intensity, and thus potentially scalable.

In emergencies, people are affected in diverse ways and require different types of supports and health services. The Sphere standards and the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Guidelines on MHPSS in Emergency Settings both underline that humanitarian assistance should address mental health and psychosocial issues through intersectoral actions, which may include informal and community-led supports, as well as more formal mental health services integrated within wider health systems. These guidelines outline the essential importance of making basic clinical mental health care available at every health-care facility and complementing these services with a range of other MHPSS response activities. It is crucial that MHPSS activities in the preparedness and acute response phases contribute to quick recovery and long-term resilience by integrating into sustainable local mental health systems.

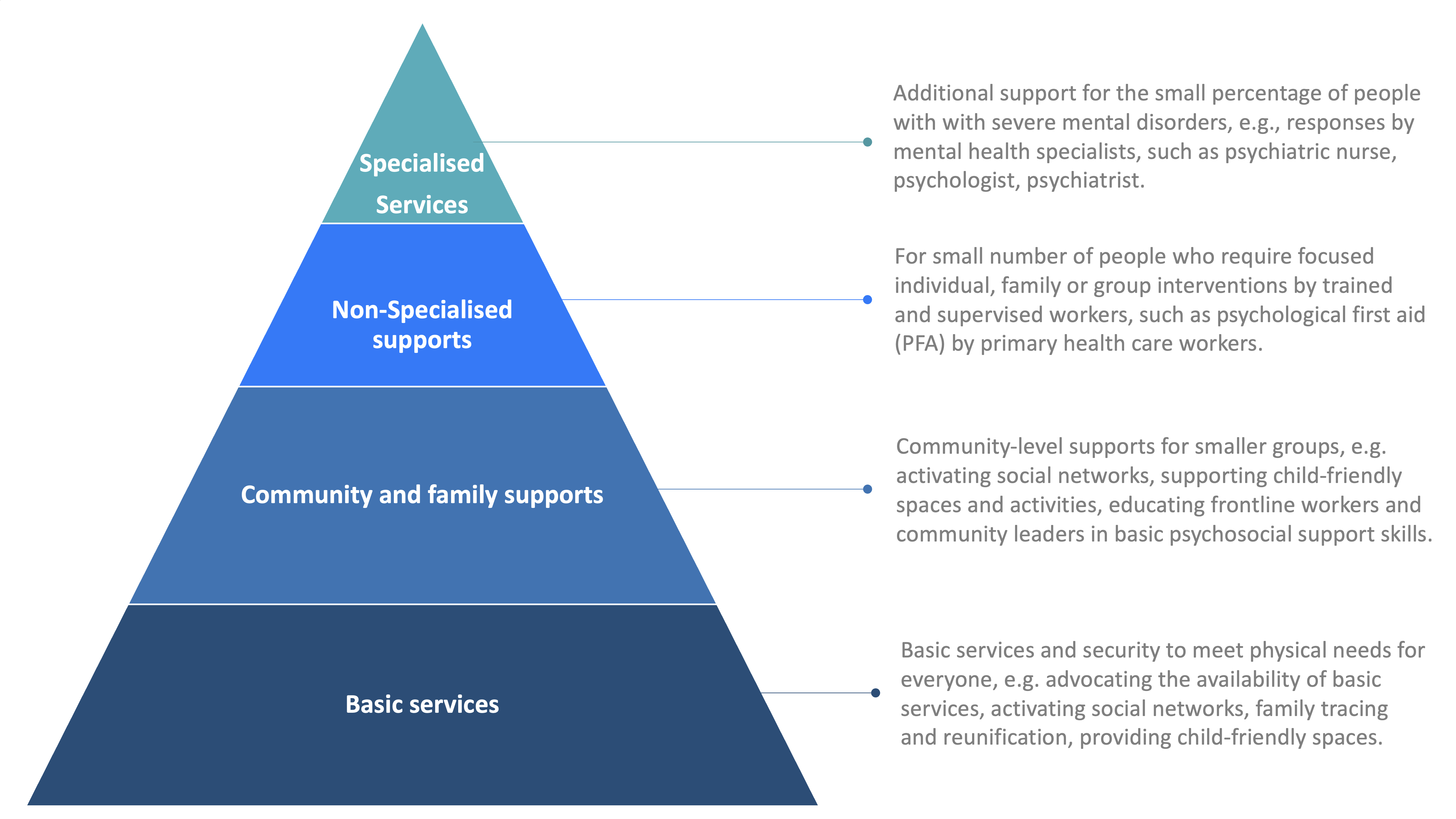

MHPSS Intervention Pyramid

The MHPSS intervention pyramid developed by the IASC (2007) is frequently used to describe the range of complementary supports for MHPSS. The pyramid includes 4 layers of complementary supports: all services are important and should be made available concurrently (see Figure 1). It is important to consider the needs of target audience and some key factors to maximise the impact of interventions when planning most suitable interventions for specific population groups.

Figure 1. MHPSS Intervention Pyramid

Adapted from IASC Guidelines, 2007[2]

Relevant Tools

-

MHPSS Minimum Services Package

The MHPSS Minimum Services Package (MHPSS MSP) is a comprehensive package, developed by WHO, UNHCR UNICEF and UNFPA. It outlines a set of high-priority MHPSS activities in meeting the immediate critical needs of emergency-affected populations. The MHPSS MSP has been field tested in 5 countries experiencing humanitarian crisis and is being implemented in many others. Use of the MHPSS MSP is expected to lead to better-coordinated, more predictable and more equitable responses that make effective use of limited resources and thus improve the scale and quality of programming.

Recovery and Rebuilding / After Acute Response Phase

The mental health impacts of major crisis can be long lasting. MHPSS interventions in this phase should offer practical support and good quality information on economic, social, health, skill, political, and environmental domains that are appropriate to the local context and resources.

Building Back Better is a concept to capture emergencies, while tragic, as opportunities to build better mental health care systems. The surge of aid, sudden focused attention to the mental health of those affected and the often higher political will that accompanies emergencies creates unique opportunities to transform mental health care for the longer-term. WHO’s report Building Back Better: Sustainable mental health care after Emergencies describes how some countries have capitalized on this momentum to transform mental health systems for their populations.

As part of Building Back Better, Community self-help and social support should be strengthened, for example by creating or re-establishing community groups in which members solve problems collaboratively. It also includes reinforce community-driven activities such as emergency relief or learning new skills and ensuring the involvement of people who are vulnerable and marginalized, including people with mental disorders.

-

Case Study 1: Assessing the long-term impact of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes, Japan (Rewrite)

A WKC funded interventional study on the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes examined the impact of a two-day therapeutic programme, including a psychoeducation intervention, individual consultations, and a small-group psychotherapy, among healthcare and social service providers. This study indicated that the proportion of healthcare and social providers with PTSD was reduced by half following the interventions.

Learn more about MHPSS interventions in emergencies (open WHO)

|

OpenWHO: Introducing Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) in emergencies WHO developed an online orientation course to strengthen the competencies of health sector actors working in emergencies to establish, support and scale up Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) in countries. |

References

[1] Kayano, R., Lin, M., Shinozaki, Y., Nomura, S., & Kim, Y. (2022). Long-Term Mental Health Support after Natural Hazard Events: A Report from an Online Survey among Experts in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), Art. 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053022

[2] WHO. (2022). Mental health in emergencies. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-in-emerg…

[3] Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), (2007) IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings, 2007. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-task-force-mental-health-… [accessed 15 June 2023]

[4] Newnham EA, Ho JY, Chan EYY. (2022). Chapter 2.5: Identifying and engaging high-risk groups in disaster research. In: WHO guidance on research methods for health emergency and disaster risk management, revised 2022. World Health Organization. pp. 37-134. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/363502 (accessed 15 June 2023).

[6] Pfefferbaum, B., Sweeton, J. L., Newman, E., Varma, V., Noffsinger, M. A., Shaw, J. A., Chrisman, A. K., & Nitiéma, P. (2014). Child disaster mental health interventions, part II. Disaster Health, 2(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.4161/dish.27535