On 28 May 2019, a five-judge bench of the Constitutional Court of Uganda unanimously rejected a legal challenge brought by British American Tobacco (BAT) against the Tobacco Control Act 2015 of Uganda. In doing so, the court affirmed that the Tobacco Control Act was enacted in order for the state to meet its obligations to protect the fundamental rights to life, health, and a clean and healthy environment. It also strongly criticised the litigation as part of a global strategy by tobacco companies to undermine public health legislation in order to increase their profits at the expense of public health.

The Tobacco Control Act is a comprehensive tobacco control law to implement the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, including provisions providing for smoke-free public places, graphic health warnings covering 65% of the principal display areas, a total ban on advertising, promotion and sponsorship, and provisions protecting public policies from tobacco industry influence and providing for the liability of tobacco companies and their directors for breaches of the Act. British American Tobacco had challenged the Act as violating its rights to property and its freedom to practice a lawful trade, occupation or business. It additionally argued that the graphic health warnings violated intellectual property rights, both as part of its constitutional right to property claim and separately under the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements.

The court comprehensively rejected BAT’s arguments, finding in favour of the Republic of Uganda and the civil society intervener, the Centre for Health, Human Rights and Development (CEHURD), on all grounds. Among the court’s findings were that:

- As products which kill their users and those exposed to tobacco smoke, tobacco products infringe on the right to life under article 22 of the Ugandan Constitution. Article 22 imposes a duty on the state to make laws and policies to protect citizens’ right to life (p.42).

- The right to life ‘cannot be separated from the enjoyment of good health’ (p.42).

- The state also has a duty under the Constitution to ensure the right to a clean and healthy environment, which includes the right to clean air free from tobacco smoke and other air pollutants (p.43).

- The Tobacco Control Act was enacted by Uganda with the objective of implementing the WHO FCTC and meeting its duties under the right to life (pp.35-36, 42). In enacting the Act, Uganda was putting into effect the provisions of its constitution which protect the rights of its citizens (p.42).

- The objective of protecting health and life under the Tobacco Control Act is sufficiently important to warrant limiting BAT’s right to engage in lawful occupation, trade or business (p.43).

On the graphic health warnings specifically, the Court found that:

- The 65% graphic health warnings are clearly designed to achieve the Act’s objectives and do not go beyond what is required; it is common in free and democratic countries to have larger warnings and ‘no cogent evidence’ was provided by BAT that the graphic health warning requirement was irrational, arbitrary or unjustifiable in light of the ‘glaring evidence’ in support of the warning requirements (p.43).

- There is no right to use a trademark, which provides only the right to exclude third parties from use. As such, graphic health warnings do not infringe on trademark rights, and in any case such limitations would be justified. (pp.45-46).

On the smoke-free public places provision, the Court found that:

- The restrictions on where smoking could take place were ‘not unreasonable, vague, uncertain or in any way a hindrance, to the economic rights of the Petitioner’ (p.46)

- The adverse effects of tobacco on the smoking and non-smoking public, including children, ‘demonstrates clearly the requirement for strategies and legislative measures, to protect the public from the adverse effects of the Petitioner’s products. … This legislative objective cannot be attained without limiting the rights of the Petitioner [in carrying out its business]’ (p.48).

- Rights to property are not absolute rights and are held subject to law – ‘[a]ll businesses are carried out subject to licence and regulation’ – and the limitations imposed by the Act are justified in a free and democratic society (p.48).

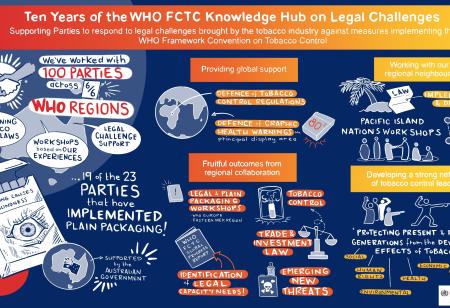

The Court also noted that the petition was one of many cases brought around the world ‘to influence policy and thwart effective legal and policy framework world-wide’ (p.50). After reviewing jurisprudence from other countries, it noted that in ‘almost all of them the arguments of the tobacco companies are similar or the same as those advanced herein by the Petitioner in this petition’ (p.50). It also reviewed evidence on the history of tobacco company efforts to undermine the WHO FCTC, and noted that it had ‘no doubt’ that the petition was ‘part of a global strategy by the Petitioner and others engaged in the same or related trade to undermine legislation in order to expand the boundaries of their trade and increase their profits irrespective of the adverse health risks their products pose to human population’ (p.53).

The Court concluded by dismissing the petition in its entirety, ‘as it has neither merit nor substance’, and ordered BAT to pay costs ‘to the respondents who were unduly burdened to defend [the petition]’ (p.54).

The Court’s judgment is notable for its detailed engagement with human rights law. It is also one of many cases (including a WTO panel report) that reject tobacco company arguments relating to intellectual property rights.

A judgment of the Constitutional Court of Uganda may be appealed to the Supreme Court. It is not confirmed at this stage whether BAT will pursue an appeal.