National Reporting Instrument 2024

Background

Adopted in 2010 at the 63rd World Health Assembly (WHA Res 63.16), the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel (“the Code”) seeks to strengthen the understanding and ethical management of international health personnel recruitment through improved data, information, and international cooperation.

Article 7 of the Code encourages WHO Member States to exchange information on the international recruitment and migration of health personnel. The WHO Director General is mandated to report to the World Health Assembly every 3 years.

WHO Member States completed the 4th round of national reporting in May 2022. The WHO Director General reported progress on implementation to the 75th World Health Assembly in May 2022 (A75/14). The report on the fourth round highlighted the need to assess implications of health personnel emigration in the context of additional vulnerabilities brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. For this purpose, the Expert Advisory Group on the relevance and effectiveness of the Code (A 73/9) was reconvened. Following the recommendations of the Expert Advisory Group, the Secretariat has published the WHO health workforce support and safeguards list 2023.

The National Reporting Instrument (NRI) is a country-based, self-assessment tool for information exchange and Code monitoring. The NRI enables WHO to collect and share current evidence and information on the international recruitment and migration of health personnel. The findings from the 5th round of national reporting will be presented to the Executive Board (EB156) in January 2025 in preparation for the 78th World Health Assembly.

The deadline for submitting reports is 31 August 2024.

Article 9 of the Code mandates the WHO Director General to periodically report to the World Health Assembly on the review of the Code’s effectiveness in achieving its stated objectives and suggestions for its improvement. In 2024 a Member-State led expert advisory group will be convened for the third review of the Code’s relevance and effectiveness. The final report of the review will be presented to the 78th World Health Assembly.

For any queries or clarifications on filling in the online questionnaire please contact us at WHOGlobalCode@who.int.

What is the WHO Global Code of Practice?

Disclaimer: The data and information collected through the National Reporting Instrument will be made publicly available via the NRI database (https://www.who.int/teams/health-workforce/migration/practice/reports-database) following the proceedings of the 78th World Health Assembly. The quantitative data will be used to inform the National Health Workforce Accounts data portal (http://www.apps.who.int/nhwaportal/).

Disclaimer

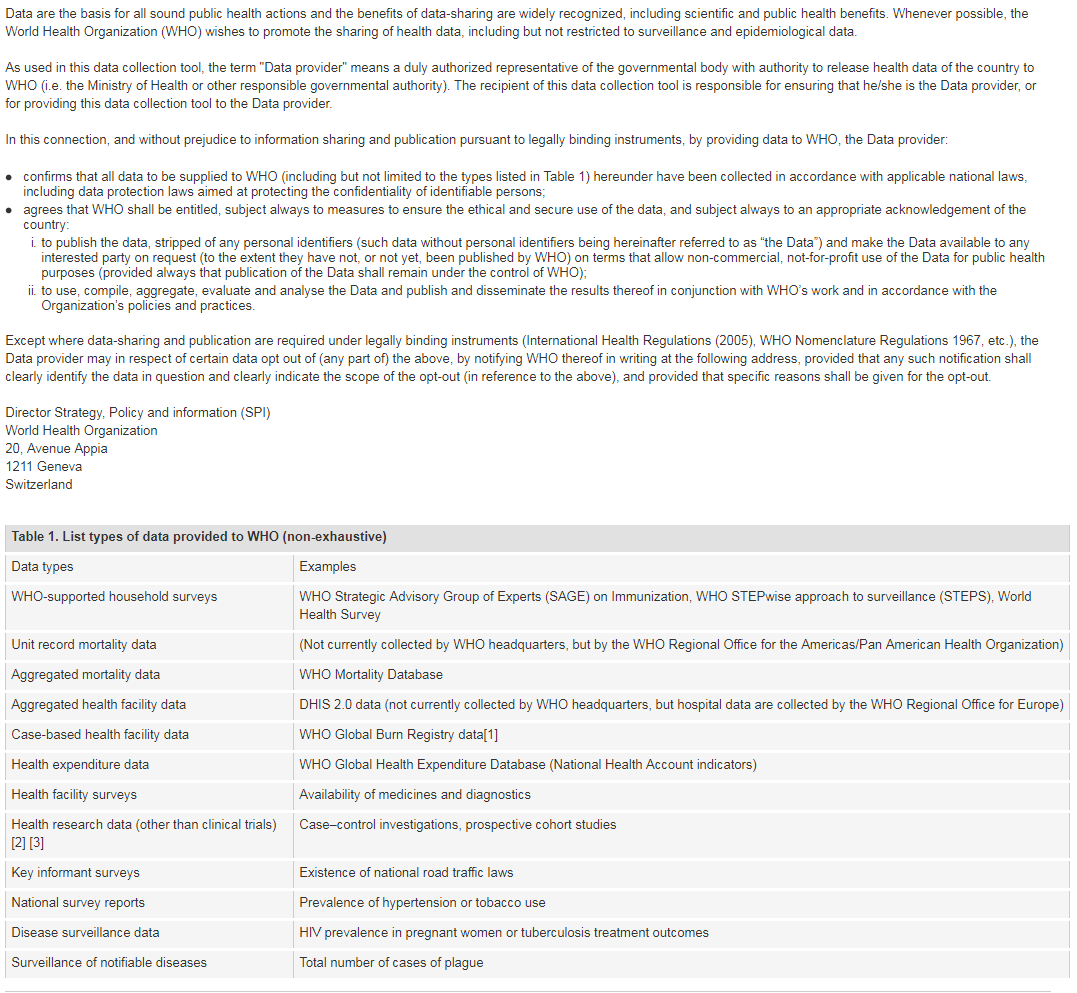

[1] Note: Case-based facility data collection as that in the WHO Global Bum Registry does not require WHO Member State approval.

[2] The world health report 2013: research for universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013 (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85761/2/9789240690837_eng.pdf)

[3] WHO statement on public disclosure of clinical trial results: Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 (http://www.who.int/ictrp/results/en/, accessed 21 February 2018).

For more information on WHO Data Policy kindly refer to http://www.who.int/publishing/datapolicy/en/

Contact Details

Contemporary issues

Like many other countries around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic increased strain on the US Healthcare system. There has been significant reporting about US healthcare facilities trying to recruit foreign healthcare workers to meet demand. Generally, employers who wish to hire a foreign worker to work permanently in the U.S. must obtain a permanent labor certification from the Department of Labor (DOL). However, for Schedule A occupations, DOL has predetermined that there are not sufficient U.S. workers who are able, willing, qualified, and available, and the employer may directly submit a petition to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) with a DOL labor certification. DOL’s Schedule A list currently includes physical therapists and professional nurses.

Health Personnel Education

Check all items that apply from the list below:

sectors on the international recruitment and migration of health personnel, as well as to publicize the Code, among relevant ministries, departments and agencies,

nationally and/or sub-nationally.

processes and/or involve them in activities related to the international recruitment of health personnel.

personnel authorized by competent authorities to operate within their jurisdiction.

Government Agreements

Responsibilities, rights and recruitment practices

Please check all items that apply from the list below:

Please check all items that apply from the list below:

International migration

| Direct (individual) application for education, employment, trade, immigration or entry in country |

Government to government agreements that allow health personnel mobility |

Private recruitment agencies or employer facilitated recruitment |

Private education/ immigration consultancies facilitated mobility |

Other pathways (please specify) | Which pathway is used the most? Please include quantitative data if available. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Nurses | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Midwives | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Dentists | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Pharmacists | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Direct (individual) application for education, employment, trade, immigration, or entry in the destination country |

Government to government agreements that allow health personnel mobility |

Private recruitment agencies or employer facilitated recruitment |

Private education/ immigration consultancies facilitated mobility |

Other pathways (please specify) | Which pathway is used the most? Please include quantitative data if available. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Nurses | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Midwives | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Dentists | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pharmacists | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other occupations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Recruitment & migration

Improving the availability and international comparability of data is essential to understanding and addressing the global dynamic of health worker migration. Please consult with your NHWA focal point, if available, to ensure that data reported below is consistent with NHWA reporting*.

(The list of NHWA focal points is available here. Please find the focal point(s) for your country from the list and consult with them.)

For countries reporting through the WHO-Euro/EuroStat/OECD Joint data collection process, please liaise with the JDC focal point.

Inflow and outflow of health personnel

Stock of health personnel

For the latest year available, consistent with the National Health Workforce Accounts (NHWA) Indicators 1-07 and 1-08, please provide information on the total stock of health personnel in your country (preferably the active workforce), disaggregated by the place of training (foreign-trained) and the place of birth (foreign-born).

This information can be provided by one of the following two options:

Technical and financial support

| Country supported | Type of support (please specify) | |

|---|---|---|

| Global (LMICs) | The United States, through USAID, supports countries developing a health workforce to help achieve global goals for controlling the HIV/AIDS epidemic, preventing child and maternal deaths and combating infectious disease threats, and supporting country goals for advancing primary health care to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and for Global Health Security. Investments are expansive and of global focus and cut across all global health program investments and can also be incorporated within sector programming to support linked efforts to provide humanitarian assistance and advance economic growth, inclusive development, democracy and human rights. Technical assistance is provided through standalone central and bilateral awards that span investment areas that include: 1) building country institutional capacity to effectively manage and finance health worker production, recruitment, supervision, employment, retention and performance; 2) building individual health worker capacity through training and skills building to provide high quality service provision; 3) developing and implementing policies to advance the support and protection of health workers and strengthen enabling workplace environments including occupational and workplace safety, gender-based violence, and labor and social protections for decent work and fair remuneration; 4) and expanding use of technology to support health workers to deliver services (e.g. digital devices, telehealth) and advance utilization of human resources data for planning and management (e.g. human resource information system / HRIS). In certain programmatic contexts, USAID support includes provision of HRH remuneration to fill critical staffing gaps impeding immediate service delivery needs that can be used to expand the overall health workforce through transition of staff to permanent employment within the country's health system. Interventions to address specific skill building and performance support needs including use of innovations and technologies such as digital health, are also widely integrated across health programming. | |

| Global (LMICs) | These efforts align and advance the priorities of the Global Health Workforce Initiative (GHWI) launched by the White House in 2022. USAID and additional U.S. Government agency achievements can be found in year 1 and year 2 Fact Sheets. | |

| Global (LMICs) | Additionally, through the Americas Health Corps (AHC), USAID is working with other U.S. Government agencies and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) to train 500,000 health care workers in the Latin American and Caribbean region over five years (2022-2027). During the first two years of AHC, the initiative has trained nearly 263,000 health workers across 22 countries in the Latin America and Caribbean region. This includes USAID training activities providing direct support for nearly 104,000 health workers including epidemiologists, community health workers, and medical staff that focused on surveillance, community-level prevention, and HIV clinical management. | |

| Global (LMICs) | The United States, through USAID, has worked to build the capacity of countries experiencing fragility, conflict, or violence (FCV) in International Health Regulations (IHR) through its support to the WHO Health Emergencies Program. From 2021-2023, over 1,500 participants were trained in a pilot training covering an overview of the IHR, Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR), understanding the role and function of a National Focal Point (NFP), and understanding preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks. |

Constraints, Solutions, and Complementary Comments

| Main constraints | Possible solutions/recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

Please describe OR Upload (Maximum file size 10 MB)