National Reporting Instrument 2018

Background

[iBG]

Adopted in 2010 at the 63rd World Health Assembly (WHA Res 63.16), the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel (“the Code”) seeks to strengthen the understanding and ethical management of international health personnel recruitment through improved data, information, and international cooperation.

Article 7 of the Code encourages WHO Member States to exchange information on the international recruitment and migration of health personnel. The WHO Director General is additionally mandated to report to the World Health Assembly every 3 years. WHO Member States completed the 2nd Round of National Reporting on Code implementation in March 2016. The WHO Director General reported progress on implementation to the 69th World Health Assembly in May 2016 (A 69/37 and A 69/37 Add.1). During the 2nd Round of National Reporting, seventy-four countries submitted complete national reports: an increase in over 30% from the first round, with improvement in the quality and the geographic diversity of reporting.

The National Reporting Instrument (NRI) is a country-based, self-assessment tool for information exchange and Code monitoring. The NRI enables WHO to collect and share current evidence and information on the international recruitment and migration of health personnel. The NRI (2018) has been considerably shortened, while retaining key elements. It now comprises 18 questions. The common use of the instrument will promote improved comparability of data and regularity of information flows. The findings from the 3rd Round of National Reporting are to be presented at the 72nd World Health Assembly, in May 2019.

The deadline for submitting reports is 15 August 2018.

Should technical difficulties prevent national authorities from filling in the online questionnaire, it is also possible to download the NRI via the link: http://www.who.int/hrh/migration/code/code_nri/en/. Please complete the NRI and submit it, electronically or in hard copy, to the following address:

Health Workforce Department

Universal Health Coverage and Health Systems

World Health Organization

20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27

Switzerland

hrhinfo@who.int

The data and information collected through the National Reporting Instrument will be made publicly available via the WHO web-site following the proceedings of the 72nd World Health Assembly. The quantitative data collected will be updated on and available through the National Health Workforce Accounts online platform (http://www.who.int/hrh/statistics/nhwa/en/).

Article 7 of the Code encourages WHO Member States to exchange information on the international recruitment and migration of health personnel. The WHO Director General is additionally mandated to report to the World Health Assembly every 3 years. WHO Member States completed the 2nd Round of National Reporting on Code implementation in March 2016. The WHO Director General reported progress on implementation to the 69th World Health Assembly in May 2016 (A 69/37 and A 69/37 Add.1). During the 2nd Round of National Reporting, seventy-four countries submitted complete national reports: an increase in over 30% from the first round, with improvement in the quality and the geographic diversity of reporting.

The National Reporting Instrument (NRI) is a country-based, self-assessment tool for information exchange and Code monitoring. The NRI enables WHO to collect and share current evidence and information on the international recruitment and migration of health personnel. The NRI (2018) has been considerably shortened, while retaining key elements. It now comprises 18 questions. The common use of the instrument will promote improved comparability of data and regularity of information flows. The findings from the 3rd Round of National Reporting are to be presented at the 72nd World Health Assembly, in May 2019.

The deadline for submitting reports is 15 August 2018.

Should technical difficulties prevent national authorities from filling in the online questionnaire, it is also possible to download the NRI via the link: http://www.who.int/hrh/migration/code/code_nri/en/. Please complete the NRI and submit it, electronically or in hard copy, to the following address:

Health Workforce Department

Universal Health Coverage and Health Systems

World Health Organization

20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27

Switzerland

hrhinfo@who.int

The data and information collected through the National Reporting Instrument will be made publicly available via the WHO web-site following the proceedings of the 72nd World Health Assembly. The quantitative data collected will be updated on and available through the National Health Workforce Accounts online platform (http://www.who.int/hrh/statistics/nhwa/en/).

[hidLabels]

//hidden: Please not delete.

Please describe

Disclaimer

[disclaim]

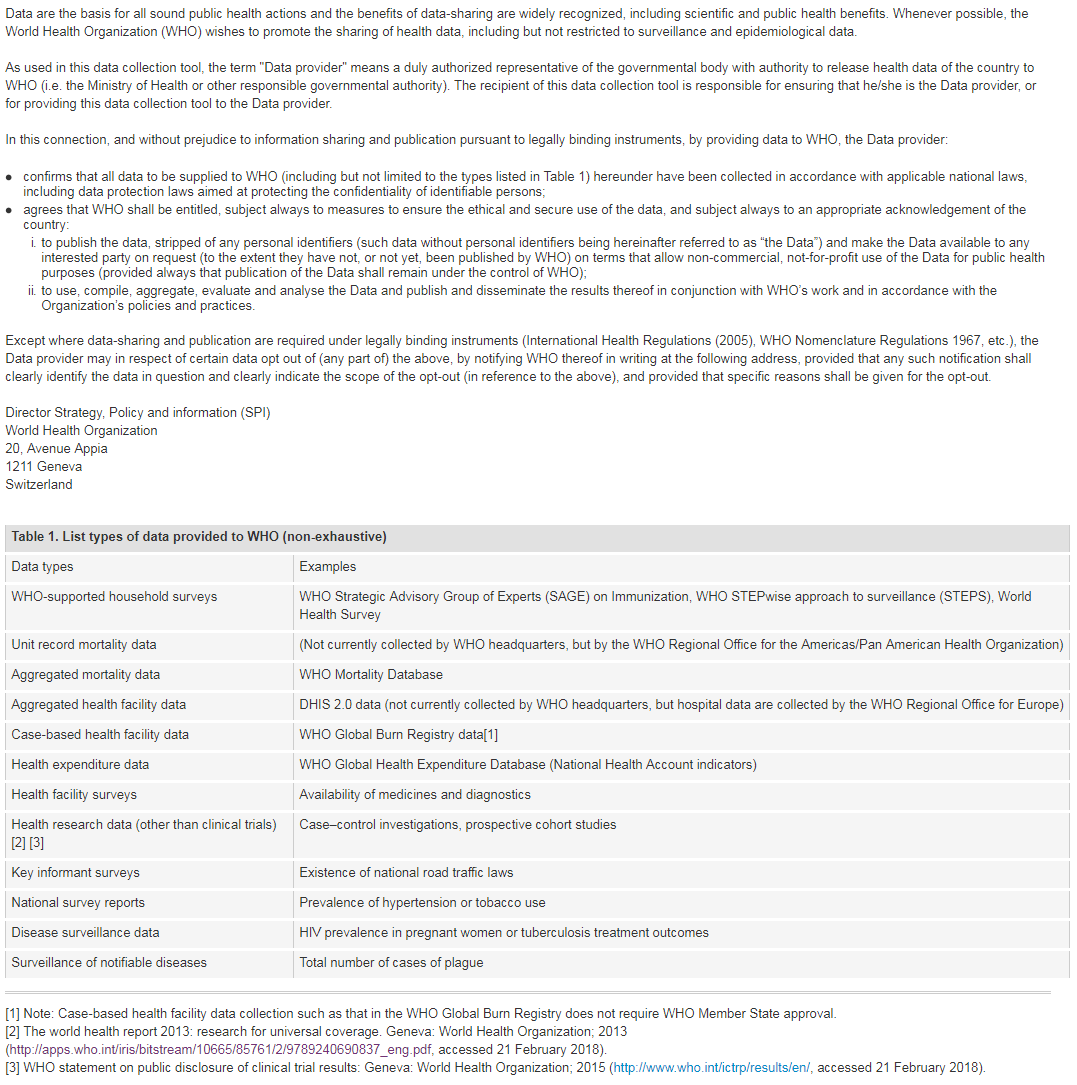

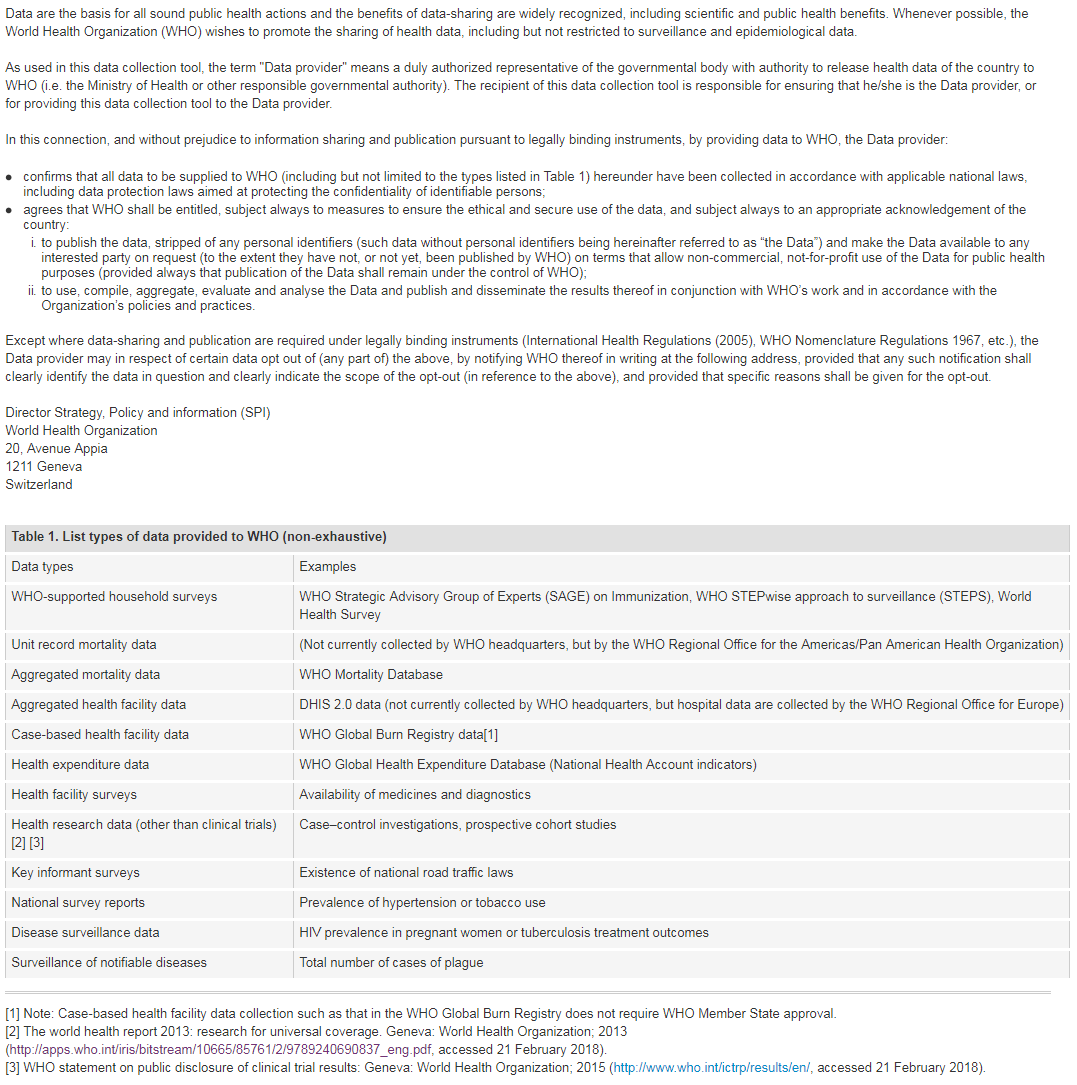

For more information on WHO Data Policy kindly refer to http://www.who.int/publishing/datapolicy/en/

For more information on WHO Data Policy kindly refer to http://www.who.int/publishing/datapolicy/en/

I have read and understood the WHO policy on the use and sharing of data collected by WHO in Member States outside the context of public health emergencies

Designated National Authority Contact Details

[q01a]

Name of Member State:

United States of America

[q01b]

Contact information:

Full name of institution:

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Name of designated national authority:

Peter Schmeissner & Kerry Nessler

Title of designated national authority:

Director, Multilateral Relations, Office of Global Affairs & Director, Office of Global Health, Department of Health and Human Services

Telephone number:

+1 202-205- 5805 & +1 301-443-2741

Email:

Peter.Schmeissner@hhs.gov &KNessler@hrsa.gov

Implementation of the Code

[q1]

1. Has your country taken steps to implement the Code?

Yes

[q2]

2. To describe the steps taken to implement the Code, please tick all items that may apply from the list below

2.a Actions have been taken to communicate and share information across sectors on the international recruitment and migration of health personnel, as well as to publicize the Code, among relevant ministries, departments and agencies, nationally and/or sub-nationally.

The U.S. Government provides updates on the Code implementation and U.S. support of the voluntary nature of the principles and practices of the Code across relevant government agencies, particularly in preparation for related topics in governance meetings of the WHO and its Regional Offices. In addition, Co-National Authorities (Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Secretary, Office of Global Affairs and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Office of Global Health) meet with stakeholders and provide to the U.S. public opportunities to inform and share comments on implementation of the Code. A Code of Practice Task Force of relevant government agencies has been formed to routinely review and share updates to the implementation of the Code.

2.b Measures have been taken or are being considered to introduce changes to laws or policies consistent with the recommendations of the Code.

In the United States, there is no federal law regulating placement agencies or employment contracts overall. Rather, public authorities regulate certain aspects of private recruitment and employment contracts, as set forth in the requirements for temporary migrant labor programs. Some states have introduced or are developing legislation to expand protections that may apply to health personnel. For example, current California law includes a mandated registration program designed to regulate foreign labor contractors who perform specified recruiting and soliciting activities of foreign workers for employment in the state (http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billCompareClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140SB477). A proposed rule regulating foreign labor contractors: (https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/regulation_detail/FLCR.html) would establish standards for the registration program that further specify who is covered by the permit requirement, set a registration fee, spell out what information must be provided on permit applications, and establish criteria for processing permit applications and permit renewals.

2.c Records are maintained on all recruiters authorized by competent authorities to operate within their jurisdiction.

As noted previously, there is no federal law regulating placement agencies or employment contracts overall. However, the regulations for the H-2B program, for the hiring of nonimmigrants to perform nonagricultural labor or services on a temporary basis, requires employers to submit their foreign worker recruitment contracts to the Department of Labor, and those agreements must contain a prohibition against charging the foreign worker recruitment fees. The Department of Labor also maintains a publicly available list of agents and recruiters who are party to such contracts and the locations in which they are operating. For more information, please see: https://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/Foreign_Labor_Recruiter_List.cfm Additionally, the Department of Labor’s Office of Foreign Labor Certification’s (OFLC) produces an annual report (https://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/performancedata.cfm) that includes data on Permanent Labor Certification and Temporary Nonimmigrant Labor Certifications. It includes information on labor certifications by occupation, visa category, and average wages in its State Employment-Based Labor Certification Profiles, information on STEM-related occupations in the labor certification programs, and top Country Employment-Based Immigration Profiles.

2.d Good practices, as called for by the Code, are encouraged and promoted among recruitment agencies.

Although the United States does not have a federal law regulating recruitment agencies overall, there are some safeguards in place to help combat fraudulent and unscrupulous recruitment practices. For example, current H2-B regulations generally prohibit the collection of recruitment fees or labor certification expenses and require that employers disclose to workers the terms and conditions of the job, and provide the Department of Labor copies of contracts with their recruiters, and the names and locations of all subsidiary recruiters. The Department of Labor maintains a publicly available list of agents and recruiters. Remedies for violations include reimbursement of unlawfully collected fees to workers, civil money penalties, and debarment from these programs where appropriate. In the permanent labor certification program, current regulations prohibit employers from seeking or receiving payments of any kind for any activity related to obtaining permanent labor certification, whether as an incentive or inducement to filing, or reimbursement for costs incurred in preparing or filing a permanent labor certification application. The kinds of payments that are prohibited include monetary payments, wage concessions, kickbacks, bribes, or tributes, in-kind payments, and free labor. Additionally, U.S. labor and employment laws relating to wages, working conditions, and anti-discrimination generally apply to all workers. Enforcing labor and employment laws for all workers can help decrease their vulnerability to various forms of exploitation, including human trafficking. It can also level the playing field for employers who meet their obligations under the law.

2.e Measures have been taken to consult stakeholders in decision-making processes and/or involve them in activities related to the international recruitment of health personnel.

While not focused specifically on recruitment of health personnel, the Department of Labor’s Office of Foreign Labor Certification (OFLC) offers several opportunities for stakeholder consultation in relation to the temporary and permanent labor programs. OFLC conducts quarterly stakeholder meetings, at which stakeholders may raise questions or issues on any of the programs the Office administers. In addition, when promulgating regulations, proposed rules are submitted for public notice and comment and the agency must respond to public comments received during the notice and comment period when issuing the final rule.

2.f Other steps:

[q3]

3. Is there specific support you require to strengthen implementation of the Code?

3.a Support to strengthen data and information

3.b Support for policy dialogue and development

3.c Support for the development of bilateral agreements

3.d Other areas of support:

No support is required. However, the U.S. Government routinely considers efforts to strengthen data and support the education, training, distribution, retention, and sustainability of the health workforce.

Data on International Health Personnel Recruitment & Migration

[iq4]

Improving the availability and international comparability of data is essential to understanding and addressing the global dynamic of health worker migration.

[q4]

4. Does your country have any mechanism(s) or entity(ies) to maintain statistical records of foreign-born and foreign-trained health personnel?

Yes

[q4x1]

Please describe:

The Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration partners with various health professional licensing organizations to assist with the data for health personnel whose professional qualification was obtained overseas.

[iQ5]

For the latest year available, consistent with the National Health Workforce Accounts (NHWA) Indicators 1-07 and 1-08, please provide information on the total stock of health personnel in your country (preferably the active workforce), disaggregated by the country of training (foreign-trained) and the country of birth (foreign-born). Please consult with your NHWA focal point, if available, to ensure that data reported below is consistent with NHWA reporting.

[q5x1]

5. Data on the stock of health personnel, disaggregated by country of training and birth

5.1 Consolidated stock of health personnel

5.1 Consolidated stock of health personnel

| Total | Domestically Trained | Foreign Trained | Unknown Place of Training | National Born | Foreign Born | Source* | Additional Comments# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Doctors | 862,965 | 647,335 | 215,630 | AMA | Data includes the domestic and foreign-trained physicians obtained from the American Medical Association (AMA). Country of Birth data is not currently available. | |||

| Nurses | 7,621 | NCSBN | Data reflects the number of nurses who took the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) licensure examinations, obtained a recognized qualification in nursing in another country, and are working as a nurse in the United States. Domestically trained data and Country of Birth data is not currently available. | |||||

| Midwives | ||||||||

| Dentists | ||||||||

| Pharmacists |

[iq5x2]

5.2 Country of training for foreign-trained health personnel

Please provide detailed data on foreign-trained health personnel by their country of training, as consistent with NHWA Indicator 1-08. This information can be provided by one of the following two options:

Please provide detailed data on foreign-trained health personnel by their country of training, as consistent with NHWA Indicator 1-08. This information can be provided by one of the following two options:

[q5x2x2]

Option B: Uploading any format of documentation providing such information (e.g. pdf, excel, word).

Please upload file

[Q5fn]

*e.g. professional register, census data, national survey, other

#e.g. active stock, cumulative stock, public employees only etc.

#e.g. active stock, cumulative stock, public employees only etc.

Partnerships, Technical Collaboration and Financial Support 1/2

[q6]

6. Has your country provided technical or financial assistance to one or more WHO Member States, particularly developing countries, or other stakeholders to support the implementation of the Code?

6.a Specific support for implementation of the Code

HHS has been implementing cooperative agreements since 2004 through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) programs. These programs all have specific objectives and program activities in many countries across Africa, the Caribbean, South America and Asia. The overall intent of these programs is to build human resource capacity for health (HRH) and strengthen health systems which in turn will encourage the retention of HRH in their countries, especially in underserved communities. Examples include: • Resilient and Responsive Health Systems (2017 – present) HRSA supports the creation of capacity building plans and the provision of technical assistance focused on the building or enhancing of organizational capacity in a variety of priority areas, including program and financial management, grants management, leadership and governance, personnel management, and evaluation and monitoring. The RRHO Initiative’s purpose is to strengthen the capacity of impact partners supported under the RRHS Initiative. The Initiative’s geographic scope includes Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan. • International AIDS Education and Training Centers (I-TECH) (2004 – present) HRSA’s I-TECH program works with foreign local partners to develop skilled health care workers and strong national health systems especially in resource limited countries. The I-TECH program provides technical assistance primarily in health workforce development, prevention, treatment and care of HIV/AIDS; operations research and evaluation; and in-country health system strengthening. I-TECH promotes local ownership to sustain effective health systems. • Twinning Programs (2004 – present) HRSA’s Twinning Programs use institution-to-institution partnerships and peer-to-peer relationships for HIV/AIDS-related human resource capacity building in PEPFAR countries. Twinning emphasizes professional exchanges and mentoring for the effective sharing of information, knowledge, and technology. Since the inception of the program, Twinning Programs have provided in-service training for more than 29,300 health and allied care providers and graduated more than 11,000 individuals from preservice programs at partner institutions. This includes training for needed mid-level cadres such as clinical associates, nurses, pharmacy technicians, lab technicians, biomedical technicians, para social workers, and social welfare assistants. • Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) (2010 – 2015) MEPI was funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the HHS/Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and the HHS/ National Institutes of Health (NIH). MEPI supports foreign institutions in Sub-Saharan African countries to develop or expand and enhance models of medical education. These models are intended to support PEPFAR’s goals of increasing the number of new health care workers by 140,000, strengthening medical education systems in the countries in which they exist, and building clinical and research capacity in Africa as part of a retention strategy for faculty of medical schools and clinical professors. From 2010 to 2015, MEPI provided grants to African institutions in 12 countries. Program activities were implemented in South Africa, Tanzania, Mozambique, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Botswana, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Ghana, and Malawi. MEPI activities have resulted in the development a network of about 30 regional partners, including in-country health and education ministries. • Nursing Educational Partnership Initiative (NEPI) (2010 – 2018) HRSA’s NEPI supports foreign nursing schools and institutions in Sub-Saharan African countries to expand the quantity, quality, and relevance of the nursing and midwifery profession to address the country’s population based health needs. HRSA’s NEPI programmatic objectives include: strengthening the capacity, quality, and effectiveness of nurse and midwifery training and education programs; identifying innovative models to increase the number of qualified health care workers; strengthening research and professional development opportunities; and developing evidence-based strategies to guide future human resources for health investments in the host countries. NEPI activities are implemented in Zambia, Malawi, Lesotho, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. NEPI supports 3-6 nursing schools in each of these countries. • Health Workforce Global Initiative (HW21) (2017 – 2021) The purpose of this initiative is to provide innovative approaches to increase adequacy, capacity, coordination, employment, complementarity, deployment, and retention of physicians, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, community health workers (CHWs), social service workers, lay health workers, laboratory technicians, and other related cadres that provide primary care and community health services to people living with HIV, tuberculosis (TB), and chronic diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, the Caribbean, and/or Latin America. HW21 is a partnership of implementing organizations with demonstrated experience building and strengthening Human Resources for Health (HRH) systems around the world. Strategic dovetailing of efforts will catalyze long-term, sustainable HRH system improvements, address priority HRH challenges at the site level to develop targeted HRH interventions, bring fresh and tested ideas to PEPFAR countries, and accelerate achievement of the 90-90-90 treatment targets. Awarded in September 2017, HW21 is a 5-year cooperative agreement funded by the HRSA with support from PEPFAR. • African Health Professions Regional Collaborate for Nurses and Midwives (ARC) (2011-2017) One of the greatest constraints to scale-up of HIV treatment in sub-Saharan Africa has been the shortage of health care personnel, and the lack of HIV/AIDS training for existing personnel. Physician shortages especially can compromise care. Task sharing is a policy by which other health care cadres (e.g., nurses, midwives, and community health workers) are able to conduct tasks and procedures otherwise set aside for physicians. Task Sharing expands opportunities for persons living with HIV to obtain needed care in a timely manner, and from a competent and compassionate workforce. The ARC project, administered in 16 Sub-Saharan countries, and 3 West African countries, assessed and addressed barriers related to nursing policy and regulations that impeded delivery of quality HIV services, and sought to improve the quality of HIV related nursing practice for pregnant and breastfeeding women and children by convening country teams of nurse and midwifery leaders for cross-collaboration and skills sharing to review nursing practices and policies within their respective countries, and make recommendations to establish task sharing and implement new scope of work for nursing practice. The country teams were assessed using a Capability Maturing Model (CMM) to track their progress on key functions, and to guide technical assistance to the country nurse teams. Results of ARC are published. • Field Epidemiology Training Program (2004 - present) Since 2004, CDC has supported more than 61 countries in the Caribbean, Africa and Asia to train health care personnel on public health principles and practices to identify and respond to communicable threats. FETP fellows learn to identify, investigate and implement solutions on such health threats as Ebola, Zika, Malaria, TB, and HIV/AIDS. Models of the program vary from short intensive 6-9 months programs, to high intensity 24-month programs equivalent to a Master’s in Public Health. FETP highlights the need to develop epidemiological technical expertise among existing health care personnel to provide national public health response, and stem the flow of infectious diseases across country boundaries. • Workforce Allocation Optimization (2013 - present) CDC assists Ministries of Health to make quality improvements to their workforce planning systems and processes by developing local capacity to create and manage registries of their health care workforce, and use of those registries to recruit, allocate and retain trained health care personnel. This effort optimizes placement of health workforce personnel in areas where their skills are most needed. Use of workforce allocation has improved not only the distribution of health care personnel within WHO member countries, but the efficiency of those health care systems to respond to HIV/AIDS. • Human Resources Information Systems (2012 – present) CDC directly assists 8 countries to develop, implement and assess the functionality of their information systems to monitor their HRH investments and share HRH data with the respective Ministries of Health, other multilateral organizations, and local in-country partners, where appropriate. These systems track critical HRH data including funding, and funders, for positions; total number of health care workers by cadre, by district, by facility; performance of facilities by staffing matrix; salary by position and range of salary by cadre; pre-and in-service training; personnel qualifications and skills. CDC provides HRIS technical assistance to other PEPFAR countries by request. In addition: The U.S. Agency for International Development has worked with all cadres of public and private sector health providers in developing countries for more than 35 years. USAID’s investments in HRH are guided by principles that support countries on their journey to self-reliance, including capacity building and enhancing sustainability through health systems strengthening (HSS). Based on these principles, USAID collaborates closely with countries to design and implement programs that will address both the quality and quantity of workers available to serve their population’s health care needs. USAID’s HRH/HSS interventions span the health system, including: data‐driven policy and planning, including human resources management; workforce development (education and training); and performance support systems to improve retention and productivity of the workforce. The interaction of human resources with other areas of the health system, such as finance and governance, is also addressed through, for example, creation of financing schemes such as vouchers, insurance, franchising, contracting out and helping providers access credit to grow health care businesses. More recent work is focused on the public health sector to develop and enhance the policy environment for expanding and fostering the role of the private health sector and its providers. For more than 25 years USAID has also supported public private partnerships in health to expand private sector products and services in developing countries. Central to these efforts is the availability of accurate and complete information on the health workforce. USAID has long supported the development and use of human resource information systems (HRIS), and most recently is collaborating with WHO on the roll-out of National Health Workforce Accounts (NHWAs). Global resources are being developed to support countries as they prepare for implementation of NHWAs, along with direct support for implementation that will allow for efficiency gains to optimize use of the existing workforce, mobilize domestic resources, and promote strategic investments for shared responsibility in HRH and health system improvements for the future.

6.b Support for health system strengthening

See 6.a above

6.c Support for health personnel development

See 6.a above

6.d Other areas of support:

[q7]

7. Has your country received technical or financial assistance from one or more WHO Member States, the WHO secretariat, or other stakeholders to support the implementation of the Code?

7.a Specific support for implementation of the Code

7.b Support for health system strengthening

7.c Support for health personnel development

7.d Other areas of support:

No assistance has been received. However, the PEPFAR Twinning Program administered through HRSA provides opportunities for information sharing amongst peers and institutions addressing HIV/AIDS related Human Resources for Health.

Partnerships, Technical Collaboration and Financial Support 2/2

[q8]

8. Has your country or its sub-national governments entered into bilateral, multilateral, or regional agreements and/or arrangements to promote international cooperation and coordination in relation to the international recruitment and migration of health personnel?

No

Health Workforce Development and Health System Sustainability

[q9]

9. Does your country strive to meet its health personnel needs with its domestically trained health personnel, including through measures to educate, retain and sustain a health workforce that is appropriate for the specific conditions of your country, including areas of greatest need?

Yes

[q9x1]

9.1 Measures taken to educate the health workforce

The HHS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Graduate Medical Education (GME) Program pays teaching hospitals to train residents in approved GME programs. Approved GME programs for which Medicare pays consist of residents in allopathic and osteopathic medicine, podiatry, and dentistry. In FY 2017, CMS is projected to pay for an estimated 85,000 to 90,000 residency slots. HRSA’s Bureau of Health Workforce implements programs and activities to train the next generation of diverse health care providers to deliver inter-professional care to underserved populations through its grants to U.S. health professions schools and training programs. Title VII programs support educational institutions in the development, improvement, and operation of educational programs for primary care physicians, physician assistants, dentists, and dental hygienists. Other sections also support community-based training and faculty development to teach in primary care specialties training. Programs include the Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Programs, Oral Health Training Programs, and Primary Care Training and Enhancement Programs. HRSA’s Bureau of Health Workforce implements through the Nursing Workforce Development Programs nursing programs with the goal to better prepare nurses to provide care for underserved populations. These programs work to improve U.S. nursing education, practice, retention, diversity and faculty development. The Advanced Nursing Education Programs aims to increase the size of the advance nursing workforce trained to practice as primary care clinicians and to provide high-quality team-based care. The Nurse Education, Practice, Quality and Retention Programs aim to expand the nursing pipeline, promote career mobility, enhance nursing practice, increase access to care and inter-professional clinical training and practice, and support retention.

9.2 Measures taken to retain the health workforce

See 9.1 above.

9.3 Measures taken to ensure the sustainability* of the health workforce

See 9.1 above.

9.4 Measures taken to address the geographical mal-distribution of health workers

HRSA’s Bureau of Health Workforce, National Health Service Corps (NHSC) Scholarship and Loan Repayment Programs provide financial, professional, and educational resources to medical, dental, and mental and behavioral health care providers who bring their skills to areas of the U.S. with limited access to health care. Since 1972, the Corps has helped build healthy communities by connecting these primary health care providers to areas of the country where they are needed most. Today, more than 10,000 NHSC members are providing culturally competent care to more than 10.7 million people at over 16,000 NHSC‐approved health care sites in urban, rural, and frontier areas. In addition, more than 1,400 students, residents, and health providers in the Corps pipeline are in training and preparing to enter practice. HRSA’s Bureau of Health Workforce administers the NURSE Corps program to provide nurses nationwide the opportunity to turn their passion for service into a lifelong career through scholarship and loan repayment programs. NURSE Corps helps to build healthier communities in urban, rural and frontier areas by supporting nurses and nursing students committed to working in communities with inadequate access to care. The NURSE Corps Loan Repayment and Scholarship Programs have helped critical shortage facilities meet their urgent need for nurses since 2002. Today, more than 1,800 NURSE Corps nurses are providing care where they are needed most and an additional 212 NURSE Corps scholarship recipients will begin their service once they complete their training. Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) and Medically Underserved Area/Population (MUA/P) are designation systems in place to assist U.S. government programs and state programs to encourage health professionals to train and practice in underserved areas. HPSA designation identifies a U.S. geographic area, population, or facility as having a shortage of providers to provide either primary care, dental, or mental health services. HPSA scores range from 0 to 25 for primary care and mental health and 0 to 26 for dental care. The higher the score, the greater the need for care. The National Health Service Corps and NURSE Corps utilize HPSA scores to identify where to place health professionals in high need areas in the U.S. CMS also uses HPSAs to help determine eligibility for Rural Health Center certification and HPSA bonus payments. MUA/P designation identifies areas and populations in the U.S. as medically underserved based on demographic and health data.

[q10]

10. Are there specific policies and/or laws, across governmental ministries, for internationally recruited and/or foreign-trained health personnel in your country?

No

[q11]

11. Recognizing the role of other parts of government, does the Ministry of Health have processes (e.g. policies, mechanisms, unit) to monitor and coordinate across sectors on issues related to the international recruitment and migration of health personnel?

Yes

[q11x1]

11.1 Please provide further information in the box below:

A Code of Practice Task Force of relevant U.S. Government agencies has been formed to routinely review and share updates to the implementation of the Code. In addition, the HRSA National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA) is a national resource for health workforce research, information, and data. NCHWA analyzes the supply, demand, distribution, and education of the U.S. health workforce. HRSA also partners with various organizations undertaking research, data collection and monitoring in health personnel migration such as:

• Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools (CGFNS) International

• Alliance for international Ethical Recruitment Practices

• Education Commission on Foreign Medical Graduates

• American Medical Association

• Association of American Medical Colleges

• National Council of State Boards of Nursing

[q12]

12. Has your country established a database or compilation of laws and regulations related to international health personnel recruitment and migration and, as appropriate, information related to their implementation?

No

[q9x3fn]

*Health workforce sustainability reflects a dynamic national health labour market where health workforce supply best meets current demands and health needs, and where future health needs are anticipated, adaptively met and viably resourced without threatening the performance of health systems in other countries (ref: Working for Health and Growth, Report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth, WHO, 2016, available from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250047/1/9789241511308-eng.pdf?ua=1

).

Responsibilities, Rights and Recruitment Practices

[q13]

13. Which legal safeguards and/or other mechanisms are in place to ensure that migrant health personnel enjoy the same legal rights and responsibilities as the domestically trained health workforce? Please tick all options that apply from the list below:

13.a Migrant health personnel are recruited internationally using mechanisms that allow them to assess the benefits and risk associated with employment positions and to make timely and informed decisions regarding them

The Department of Labor requires employers who are bringing workers to the United States temporarily on an H-1B visa to provide the workers with a copy of the Labor Condition Application (LCA) no later than when the worker reports to work. The LCA informs the foreign worker of the wage to be paid, the job title, period of intended employment, and place of employment. The LCA also informs the worker of how to file a complaint alleging misrepresentation of material facts or failure to comply with the terms listed on the LCA. The Department of Labor also requires employers who are bringing in H-2B temporary workers to provide the workers with a copy of the job order no later than when the worker applies for the visa, in a language understood by the worker, as necessary or reasonable. The H-2B job order informs the foreign worker of the job duties, period of employment, wage to be paid, any training that will be available, deductions that will be made, and how the employer will provide or pay for the cost of the worker’s transportation, among other things. Additionally, the U.S. State Department has several resources available for certain individuals traveling to the United States as temporary workers or students informing them of their legal rights and protections: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/visa-information-resources/rights.html There are no specific laws or policies for internationally recruited or trained health personnel. The U.S. federal labor and employment laws generally apply to all workers, and agencies across the federal government, such as the Department of Homeland Security, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Department of Labor, and the National Labor Relations Board frequently work together to coordinate enforcement of federal law. For example, through the conclusion of a Memoranda of Understanding (MOU), which also recognizes the importance of protecting workers who seek to assert their workplace rights from retaliation by employers, recruiters or other parties, the Departments of Homeland Security and Labor undertook coordination efforts to advance the respective missions of each agency. https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/documents/MOU-Addendum.pdf

13.b Migrant health personnel are hired, promoted and remunerated based on objective criteria such as levels of qualification, years of experience and degrees of professional responsibility on the same basis as the domestically trained health workforce

The H-1B program requires that employers first file a Labor Condition Application (LCA) with the Secretary of Labor attesting that the wage paid to the foreign worker is the higher of the actual wage rate (the rate the employer pays to all other individuals with similar experience and qualifications who are performing the same job), or the prevailing wage (a wage that is predominantly paid to workers in the same occupational classification in the area of intended employment at the time the application is filed). Similarly, H-1B employers must provide foreign workers working conditions based on the same criteria as those the employer offers to its U.S. workers, such as hours, shifts, vacation periods, and benefits. Employers wishing to bring in foreign health personnel on a permanent basis must usually obtain a labor certification from the Department of Labor determining that there are not sufficient U.S. workers who are able, willing, qualified, and available in the area of intended employment and that the employment of a foreign worker will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of workers in the U.S. similarly employed. One of the methods utilized by the Department of Labor to ensure that the wages and working conditions are not affected is to require the employer to offer at least the prevailing wage to all U.S. workers during its labor market test and then to the foreign worker upon receipt of his or her permanent residency. An employer is not required to file a labor certification application with the Department of Labor for those foreign workers (including professional nurses and physical therapists) who qualify under the Department’s Schedule A. In those cases, an employer must attach its labor certification application to the immigrant worker petition it files directly with the Department of Homeland Security. Employers who are interested in employing H-2B temporary workers must obtain a labor certification from the Department of Labor. Among other requirements, they must offer and pay the H-2B worker no less than the highest of the prevailing wage, the applicable Federal minimum wage, the State minimum wage, or local minimum wage during the entire period of the approved H-2B labor certification.

13.c Migrant health personnel enjoy the same opportunities as the domestically trained health workforce to strengthen their professional education, qualifications and career progression

No. Foreign workers do not necessarily have the same education and training opportunities as national workers, as some federal funding streams have limitations on the non-U.S. citizen individuals that can access them. However, migrant health personnel may enroll in private educational courses the same as the domestically trained health workforce, and employer-provided training may be provided to domestic and migrant health personnel equally.

13.d Other mechanisms, please provide details below if possible:

For more information, please visit the following websites: 1. Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Act: http://travel.state.gov/content/visas/english/general/rights-protections-temporary-workers.html 2. Link to H1B visa protections, 20 CFR Part 655, Subparts H and I: http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/textidx?SID=96b00af0b6b7ce8e8fda30ea4c512a6f&node=20:3.0.2.1.28&rgn=div5 - 20:3.0.2.1.28.2#sp20.3.655.h 3. The U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety & Health Administration: http://www.osha.gov/law-regs.html 4. The U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division: http://www.dol.gov/whd/ 5. The U.S. Department of Labor Office of Foreign Labor Certification: http://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/ 6. The U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics: https://www.bls.gov/

[q14]

14. Please submit any other comments or information you wish to provide regarding legal, administrative and other measures that have been taken or are planned in your country to ensure fair recruitment and employment practices of foreign-trained and/or immigrant health personnel.

No other comment

[q15]

15. Please submit any comments or information on policies and practices to support the integration of foreign-trained or immigrant health personnel, as well as difficulties encountered.

No other comment

[q16]

16. Regarding domestically trained/ emigrant health personnel working outside your country, please submit any comments or information on measures that have been taken or are planned in your country to ensure their fair recruitment and employment practices, as well as difficulties encountered

No other comment

Constraints, Solutions, and Complementary Comments

[q17]

17. Please list in priority order, the three main constraints to the implementation of the Code in your country and propose possible solutions:

| Main constraints | Possible solution | |

|---|---|---|

| The federal/State structure of the U.S. government and the privatized nature of the U.S. health care system limits central decision making on issues covered by the Code of Practice (COP). | The U.S. National Authority and the U.S. Interagency COP Task Force are developing relationships both across and outside of government in order to promote the voluntary principles and practices that are consistent with the spirit of the COP. Relationships are being explored with appropriate non-governmental stakeholder groups such as the Alliance for Ethical International Recruitment Practices and others. These actions are designed to foster collaboration, cooperation, and policies consistent with the COP. | |

| The independent/private health personnel recruitment process in the U.S. provides challenges to track migration trends and compile complete data and information regarding international migration and recruitment. | The U.S. National Authority and the U.S. Interagency COP Task Force are working to develop a catalogue of existing data sources and the data elements collected by each agency. This work is aided in part by the HRSA National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA). The NCHWA continues to develop more complete projection data on the supply and demand of the U.S. health workforce, including foreign-educated health workers. | |

| The legal processes and regulations related to the many aspects of migration to and obtaining employment in the U.S. are spread across a number of federal government agencies. | The U.S. Interagency COP Task Force, convened by the National Authority, brings together the variety of federal government stakeholders involved in the immigration of health personnel process. In order to increase knowledge and transparency around this issue, the National Authority is encouraging the sharing of data and information across federal government entities. |

[q18]

18. Please submit any other complementary comments or material you may wish to provide regarding the international recruitment and migration of health personnel, as related to implementation of the Code.

[q18x1]

Please upload any supporting files